A Designer’s Dilemma: Power, Privilege, and Pure intentions

Posted on November 15, 2019I am going to be completely honest: I am facing an existential crisis, a moral dilemma.

I’m here. In New York City. In the Transdisciplinary Design program. I flew halfway across the globe. To get a formal design education in the hope of completing the program and emerging with a better sense of how I could contribute to my home country – the Philippines.

Let’s backtrack.

For three years, I was working in the Philippines for a ‘social innovation’ start-up founded by a New Yorker and led primarily by a group of white men who had very little understanding of Philippine social and cultural context. Around this time last year, I made the decision to leave when I realized I was only helping the already-rich CEO get even richer rather than actually making an ‘impact’ on the Filipinos I thought I was ‘serving’.

I was disillusioned by the vision and mission that was clearly an effective recruitment strategy for the likes of me. My naive, fresh graduate self thought I was on the right path joining a company that had this grand vision of digital inclusion and bridging the digital divide in emerging markets.

It was especially appealing because I was given the opportunity to work as a UX Designer after I was introduced to “design thinking” by my former team leader who had received a design education from the United States. The reason this was so appealing was that no design programs existed when I was in college (and probably is still in its infancy in today’s Philippine education system), and I honestly did not know what ‘design’ entailed/was/could be. All I had to offer at that time was my own experience as a development communication graduate, along with my own knowledge and lived experience as a Filipina.

But in retrospect, the setting I was in was very much contributing to what Lisa Parks describes as Westerners doing feel-good research in order to ‘modernize’ and ‘enhance’ the lives of anyone fortunate enough to be part of their vanity project¹, and what Anand Giridharadas refers to as win-win-ism that elite humanitarians find themselves in as they masquerade self-interest with ‘social purpose’ ².

After roughly three years of working for that company, I had to go through deep self-reflection and introspection about my personal values and beliefs as a human and a ‘designer’. I asked myself: Who am I? Who am I as a designer? What is it that I can, could, and should offer? And for whom? This line of questioning brings to mind Teju Cole, who wrote: “if we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement” ³.

I knew I wanted to learn more about how I can responsibly participate in challenging and rethinking the problematic systems that we live in and interact with, which has brought me to where I am today.

Yet the dilemma persists.

Ever since I moved to New York, I would often be asked: “Do you plan to go back home to the Philippines?”. I’ve never been able to answer with confidence.

I somehow thought by getting a formal design education, I would emerge with a better sense of how I could contribute to my home country, especially considering the fact that this kind of education does not exist in the Philippines. However, I find myself in a position of confusion, cognitive dissonance, existential crisis, and a deep moral dilemma (well, that escalated quickly) as I reflect on how I can and should situate myself as a designer.

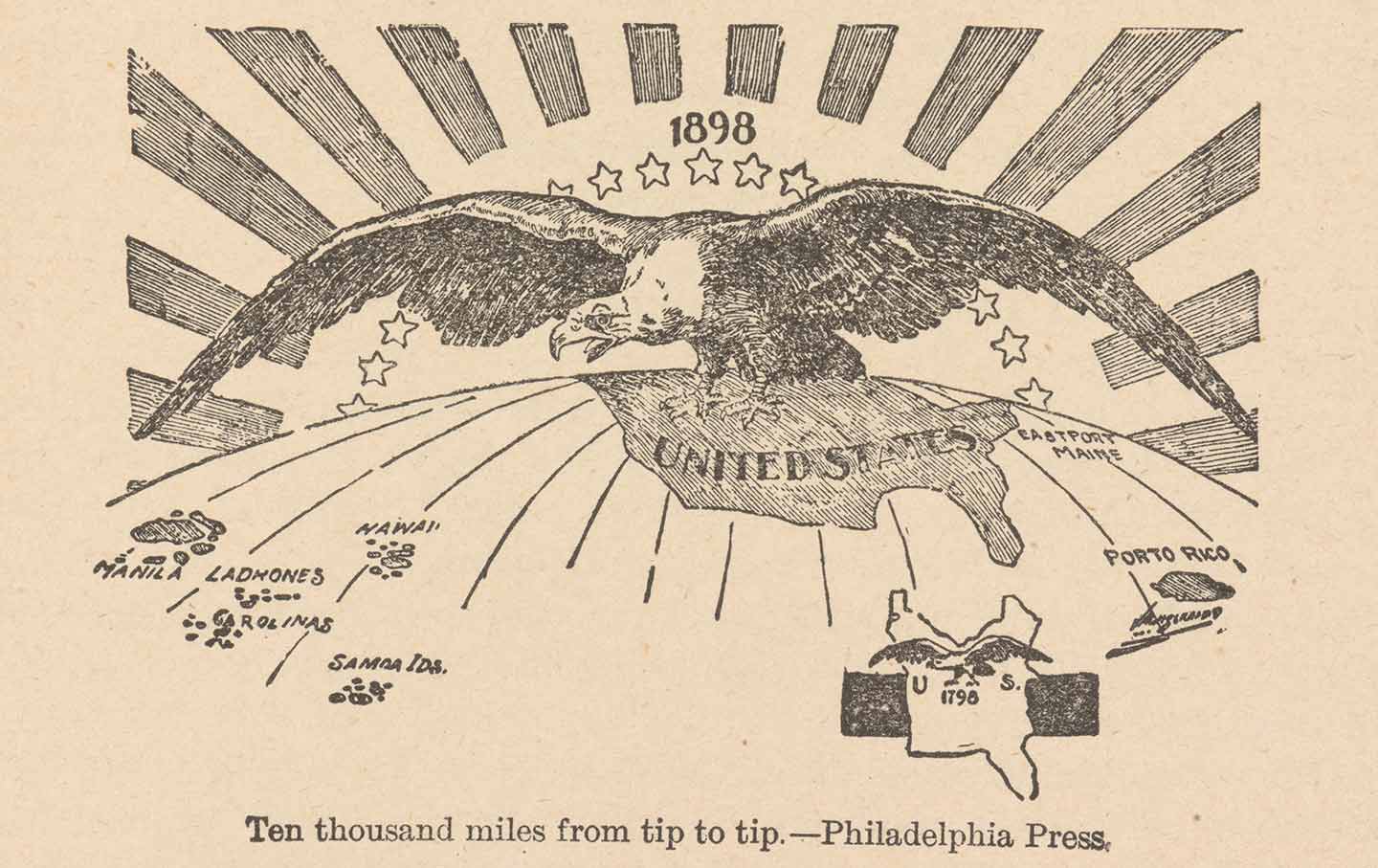

There’s something problematic about studying in a country that colonized my own country (not to mention the fact that the Philippines remains a neo-colony of the U.S. even after almost a century), and hope to fly back being ‘more equipped’ to ‘help’– in spite of pure intentions. Would I only be propagating an already atomized, plutocratic, westernized country where our own sense of our culture and nationalism is dwindling? I refuse to see myself as “superior” and “knowledgeable”…it just doesn’t sit well with me.

Ten thousand miles from tip to tip. Source: Marshall Everett

So today I find myself asking the same questions I was asking myself last year, accompanied by several more.

- How should we situate ourselves as designers?

- Do we only participate in design processes in contexts that we can appropriately identify with?

- While acknowledging our privilege and power is a good start, how should we move past acknowledgement?

- How might we think of decolonized design methods that are not predominantly informed by Western ways of thinking?

In class, Ahmed Ansari offered some ways to navigate such a dilemma. He talked about embracing opportunities to learn about other cultures so we can turn an eye towards how we fall short in our own approaches as we develop a “double” or “triple” consciousness. I think that gives me a better perspective on the value of consciously learning, unlearning, and re-learning the different socio-cultural environments we find ourselves in.

He also encouraged studying history and indigenous philosophies in order to help us think about the future, which reminded me of Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino Psychology), which is defined as “psychology born out of the experience, thought, and orientation of the Filipinos…whereby the theoretical framework and methodology emerge from the experiences of the people from the indigenous culture.” ⁴ I certainly see the potential of going back to my roots in a deep and deliberate manner in order to integrate that in my own practice.

While these are some promising ways of moving forward, I do hope to participate in a collective reflection and rethinking of ways in which we might explore the evolving role of designers (e.g. as ‘facilitators’) and identify hyper-local and genuinely participatory approaches that aren’t mere “toolkits” treated as off-the-shelf solutions.

This debilitating crisis and endless questioning we face presents an opportunity for us to be be more critical designers – we must challenge the status quo, call out the elites to give up their power, and actively participate in conversations about all roles we play in the grand scheme of things.

It takes an immense amount of courage and thoughtfulness to be a designer, or rather, to be human. But I would like to believe that recognizing that could be a fruitful point of departure.

Sources:

[1] Parks, Lisa, and Nicole Starosielski. Signal Traffic Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

[2] Giridharadas, Anand. “The Win-Win Fallacy.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, September 10, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/09/the-win-win-fallacy/569434/.

[3] Cole, Teju. Known and Strange Things. London: Faber et Faber, 2017.

[4] Pe-Pua, Rogelia, and Elizabeth A. Protacio-Marcelino. “Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino Psychology): A Legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez.” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 3, no. 1 (2000): 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839x.00054.